The tour operators enthusiastically touted travel to their country. “Peru is a beautiful, lush, and mountainous country in South America….” Describing adventures from coastal Lima to the heights of Machu Picchu, these twelve-year-olds were convincing. Having investigated the multicultural influences on the Americas from Indigenous, European, African, and Asian peoples, my students in small groups were “hired” by individual countries in Central and South America to promote tourism. Their cultural-historical immersion tours (introduced with video promos, brochures, and displays to sell their trips) were a traveler’s dream.

Changes in the Americas

Our sixth grade history course,

American

History I—Changes in the Americas, begins with

an introduction to geography and archaeology of the Americas, Africa, Asia, and

Europe. It continues with a study of pre-

and post-Columbian global exploration and exchange, Indigenous Americans,

European colonization of the Americas, African cultures and enslavement, and

the evolution of the English colonies. The course concludes with an examination

of the causes of the American Revolution and the human experience of the war.

During the course of the year, there are several small-group projects. Each student also conducts individual

research on a chosen topic in American history.

Students make history themselves as the year ends, developing Think-Care-Act Projects to change the

world.

Working closely and

cooperatively, numerous groups of sixth grade teachers have refined the course over

the years. In 2013-14 we redesigned an

existing group multimedia project, turning the project into an experiential

“campaign.” Colleagues Bert Howlin,

Steven Ramirez, Larry Henderson, and I assign young researchers to learn about

the geography and contributions of Indigenous Americans as well as European,

African and other peoples of assigned countries of the Americas. Then we “hire” these newly minted “experts,”

to create itineraries for trips focusing on the multicultural history of their

research countries. Student groups create

video promos, brochures, and displays to instruct their peers and “sell” their

trips to visitors to their tourism booths.

The Hill Fund for Faculty Enrichment & Overseas

Adventure Travel

As happens every fall

when we explore the world of the Incas of Peru, I get restless. While I love classroom exploration, I longed

to travel to Peru to see Cusco and Machu Picchu for myself and to tackle some

of the questions that arise year after year.

“Who built Machu Picchu on top of a mountain—and why?” “How did they accomplish so much in such a

short time?” “What happened to the

Incas?” With the generous support of the

Hill Fund for Faculty Enrichment, I finally made the trip to Machu Picchu,

enriching my first-hand knowledge of the vast civilizations that existed in the

Americas before European exploration. Of

particular relevance are three Hill Fund emphases: “Personal challenge/growth

experiences that will enhance one’s excellence and depth as a teacher,

colleague and member of the community; The culture of teachers teaching teachers;

A concern for global issues that extend beyond the syllabus.”

I had researched several tour companies offering trips to Peru and Machu Picchu, and Overseas Adventure Travel stood out. Online reviews and reviews from friends who had taken the trip confirmed its outstanding itinerary. Guides are of Incan heritage and have worked with the company for years. Several have master’s degrees. All have been rated as excellent guides by travelers on their trips. Most important, group sizes ranged from ten to sixteen.

Of particular relevance

to me were several aspects of this itinerary.

We’d visit Andean communities, where local guides would introduce modern

descendants of ancient Incan ancestors, whose lifestyles blend new and old. We would

visit Cusco, capital of the Incan world.

We’d have two days two explore Machu Picchu. We’d see Colonial European impact on the country. I would be able to examine first hand the

effects of ancient and modern globalization on the Incan people and on

Peru. The trip would be rigorous, with

multiple locations and five days at 7,000 to 12,500 feet of elevation. This would be a history teacher’s dream and a

personal challenge.

Blogging as Learning and Teaching: An Online Archaeological

Treasure Hunt

In past Think-Care-Act blogs, I have shared

topics promoting peace education, critical thinking, local and global empathy,

and social action in our classrooms.

This Peru blog relates to these themes in promoting a sense of global

connection and concern with today’s Peruvian highlanders (roughly half of

Peru’s population) along with appreciation for the contributions of their

ancient ancestors and how they can inform our lives today. In this blog I will share background

information, travel impressions, photos, and links for further research.

Readers

will see that I came away with more questions than I ever knew I had about

modern and ancient Peru. Since my

return, I continue to research these questions through books, websites, and

videos. I invite you to join me in an online

archaeological treasure hunt—and online course on the enduring influence of the

Incas on Peru. For each section of the

trip, I have posted links for videos, books, and websites. Find these below the

blog and use these resources for your own research. Add your comments, corrections, questions, and

insights as you travel and learn virtually.

Teachers will find these links and photos useful for classroom research

in language, history, literature, geography, arts, architecture, government, and

culture. Vámonos!

Meeting Corina Duran

A multilingual Andean

woman pursuing her doctorate in rural tourism while leading adventure travel

trips in the 11,000-foot highlands of her childhood is someone to admire. O.A.T.’s Corina Duran is a teachers’ teacher,

someone who can herd cats and teach passionately and effectively at the same

time. The cats in this case, were fourteen

Americans from twenties to sixties with a variety of backgrounds. Six were former Peace Corps volunteers in

Bolivia, Liberia, Micronesia, and Pakistan; all shared a love of global travel;

seven had just come off the Amazon.

A multilingual Andean

woman pursuing her doctorate in rural tourism while leading adventure travel

trips in the 11,000-foot highlands of her childhood is someone to admire. O.A.T.’s Corina Duran is a teachers’ teacher,

someone who can herd cats and teach passionately and effectively at the same

time. The cats in this case, were fourteen

Americans from twenties to sixties with a variety of backgrounds. Six were former Peace Corps volunteers in

Bolivia, Liberia, Micronesia, and Pakistan; all shared a love of global travel;

seven had just come off the Amazon.

Then she proceeded to lead

us on a non-stop, breathtaking march through Peru for the next ten days, from

sea level to 12,500 feet, from modern-day Lima to back-in-the-day Chinchero

near Cusco. And of course, to Machu

Picchu, enigmatic city in the clouds.

1. Lima

A city of extremes, tourist-path

Lima neighborhoods like suburban Miraflores and artsy Barranco resemble subdued,

posh, gentrifying neighborhoods in many colonial cities. However, the so-called pueblos juvenes (new towns) we glimpse on hillsides through side

streets indicate decades of rural-to-urban migration.

Unfortunately, we do not visit the communal settlement Villa El Salvador, a new town or barrio founded in 1971 by thousands of mountain people seeking safety in Lima after an earthquake. Mirroring Andean Inca family and community organization, community members created health centers, communal kitchens, sports grounds, and schools. Irrigation like that of the Incas has helped residents transform the Lima desert into cropland. Villa El Salvador is touted as an oasis for the city’s poor, and has earned a “Messenger of Peace” designation from the United Nations.

Unfortunately, we do not visit the communal settlement Villa El Salvador, a new town or barrio founded in 1971 by thousands of mountain people seeking safety in Lima after an earthquake. Mirroring Andean Inca family and community organization, community members created health centers, communal kitchens, sports grounds, and schools. Irrigation like that of the Incas has helped residents transform the Lima desert into cropland. Villa El Salvador is touted as an oasis for the city’s poor, and has earned a “Messenger of Peace” designation from the United Nations.

We hear tidbits from

locals about daily life in Lima. Overall,

corruption is a problem, but the entrance of women to the ranks of police and

garbage workers—at equal pay for equal work—has decreased the corruption and

increased productivity. We spot

countless buses from independent companies.

Drivers rent their buses, participating in the thriving informal

economy, but with no healthcare or pensions.

Locals explained that a bus driver who works from six A.M. to ten P.M.

earns about $50 (US) per day, a better rate than teachers, police, lawyers, or nurses. On our ride through the peaceful heart of the

city, we see riot police with shields up, awaiting marching doctors on strike

in the capital. While extremes of

poverty, wealth, protest, and peace are all around us, our focus is on extremes

of modernity versus antiquity.

We hear tidbits from

locals about daily life in Lima. Overall,

corruption is a problem, but the entrance of women to the ranks of police and

garbage workers—at equal pay for equal work—has decreased the corruption and

increased productivity. We spot

countless buses from independent companies.

Drivers rent their buses, participating in the thriving informal

economy, but with no healthcare or pensions.

Locals explained that a bus driver who works from six A.M. to ten P.M.

earns about $50 (US) per day, a better rate than teachers, police, lawyers, or nurses. On our ride through the peaceful heart of the

city, we see riot police with shields up, awaiting marching doctors on strike

in the capital. While extremes of

poverty, wealth, protest, and peace are all around us, our focus is on extremes

of modernity versus antiquity. The extreme on which we

focus on our first outing is of the modern city meeting the ancient city: a

former motocross playground under excavation to reveal Huaca Pucllana (Sacred Playground), one of one of an estimated 366 archaeological

sites in the city. Lima is clearly

visible all around this vast pyramidal structure, built by pre-Incan peoples

around 400 A.D. Imagine shelves of adobe-mud

“books” rising in pyramid fashion and you get a sense of this “bookshelf

construction” designed to sway, and thus withstand, earthquakes. Life-size figures dot the site, making adobe

bricks, making offerings, silently telling their story.

The extreme on which we

focus on our first outing is of the modern city meeting the ancient city: a

former motocross playground under excavation to reveal Huaca Pucllana (Sacred Playground), one of one of an estimated 366 archaeological

sites in the city. Lima is clearly

visible all around this vast pyramidal structure, built by pre-Incan peoples

around 400 A.D. Imagine shelves of adobe-mud

“books” rising in pyramid fashion and you get a sense of this “bookshelf

construction” designed to sway, and thus withstand, earthquakes. Life-size figures dot the site, making adobe

bricks, making offerings, silently telling their story.  Lima’s Lorca Museum houses

a stunning collection of pre-Columbian pottery, mummies, metalwork, and

textiles from various pre-Inca cultures.

Its website provides access to the collection and a virtual tour of

indigenous cultures of Peru.

Lima’s Lorca Museum houses

a stunning collection of pre-Columbian pottery, mummies, metalwork, and

textiles from various pre-Inca cultures.

Its website provides access to the collection and a virtual tour of

indigenous cultures of Peru.

The Northern

Peru Moche portrait-head pots, left as funerary offerings,

are as detailed as photographs, portraying men, women, diseases, animals, and minutiae

of ancient life.

The power of the

Catholic Church and the influence of the Spanish conquerors are evident

throughout Lima. The beautiful yellow Monasterio de San Francisco is under

slow renovation. It houses vast Colonial

libraries, the bones of 70,000 deceased Colonial Limans in its vast catacombs, and

a 1697 version of the Last Supper

with cuy, guinea pig, as the main

dish, a concession to Andean culture.

The power of the

Catholic Church and the influence of the Spanish conquerors are evident

throughout Lima. The beautiful yellow Monasterio de San Francisco is under

slow renovation. It houses vast Colonial

libraries, the bones of 70,000 deceased Colonial Limans in its vast catacombs, and

a 1697 version of the Last Supper

with cuy, guinea pig, as the main

dish, a concession to Andean culture.

2. Who Were the Inca?

Finding Answers in Cusco and Beyond

We arrive in Cusco

(Cuzco, Qosqo), a UNESCO World Heritage

Site, after flying over the 22,000-foot snow-capped Andes. At 10,900 feet, we have landed in the “navel

of the world,” as the Incans called it in Quechua, one of today’s official

languages of Peru. Immediately, we feel

the thinner air. Colors seem

brighter. Is it the near-Equatorial sun

against the blue sky, or is it the brilliance and resilience of Andean culture

we see all around us?

The winter solstice is

approaching, June 21, and Inca flags are flying. It’s the lead-up to the Sun Festival of Inti Raymi, on June 24. It’s the beginning of the agricultural year,

and there is a full-fledged New Year’s party in the streets. Pacing ourselves as we acclimate to altitude,

we watch university student groups of dancers perform indigenous dances before

a reviewing stand in the central plaza.

They whirl and stomp in regional costumes representing all the colors of

the Inca rainbow flag.

The Spanish

conquistadors wrote home to their king, that Cusco, a city of 15,000, was the

most magnificent city of the new world. A

modern-day archaeologist, Michael Moseley wrote that in 1493, the Inca empire

“probably surpassed…China and the Ottoman Empire as the largest nation on

earth….”

Who were the Inca? They were the Andean peoples who came to

power in the late 1400s to early 1500s, whose empire ranged from present-day Colombia

to Chile. Earlier civilizations had

risen and fallen in the region, including the Chavín, whose temples were north

of Lima, and the Nazca, who carved mysterious giant figures of monkeys,

hummingbirds, and other shapes into the southern Peruvian deserts around 500

A.D. The Moche farmed numerous crops,

developing irrigation systems before 700 A.D.

The Chimú built lengthy irrigation systems also, including a twenty-mile

canal into their massive capital of Chan Chan, home to 100,000 people.

The Inca, or Tawantinsuyu (Land of the Four Quarters),

were just another civilized group, but their rapid conquest and absorption of

other societies made their civilization the largest in South America from the

1400s-1500s. While a conquest-based,

hierarchical society, the Inca were also a sharing-based culture. The tight control held by Incan rulers, their

nobles, and their administrators kept the hierarchy in power, but also ensured

that all members of society had food, clothing, housing, and care from

childhood to old age.

Everyone worked. Community work was mandated through an elaborate

mit’a tax system, and shares of the

fruits of one’s labors were portioned out to the state, the community, and the

family. Men and women had equal status in some areas, while men were favored in

most. There was no money; they had a

barter society of services and goods.

Family groups were organized into ayllus,

which owned property on behalf of the group.

Through this highly organized society, everyone—noble and commoner, male

and female, young and old—had specific obligations to the family, community,

and state. Men devoted time for the

empire in the army and massive road and building projects. Women developed the weaving still practiced and

valued in the area today.

Everyone worked. Community work was mandated through an elaborate

mit’a tax system, and shares of the

fruits of one’s labors were portioned out to the state, the community, and the

family. Men and women had equal status in some areas, while men were favored in

most. There was no money; they had a

barter society of services and goods.

Family groups were organized into ayllus,

which owned property on behalf of the group.

Through this highly organized society, everyone—noble and commoner, male

and female, young and old—had specific obligations to the family, community,

and state. Men devoted time for the

empire in the army and massive road and building projects. Women developed the weaving still practiced and

valued in the area today.

While each ayllu had religious traditions, the

state’s spiritual energies were focused on the Creator, Viracocha, as well as Inti,

the Sun god. They held sacred Pachamama (Mother Earth), as well as the

moon and gods of thunder, rainbows, and the mountain spirits, or Apus.

Indeed, as the ruler or Sapa Inca

began to be identified with Inti, the

Sun god, the state religion supported his conquests as head of state. Imperialists, the Incas folded competing

peoples into the swiftly expanding empire using a carrot and stick approach of

negotiation, gifts, and intermarriage or military attack, defeat, and massive resettlement.

3. Pachacuti’s Projects

How is it possible that

the Incan empire was so short-lived (1438-1532), yet its architectural remains

are so massive and long lasting? In a

society where work and stone are sacred, perhaps massive building projects

should be expected. But they were not

undertaken until the ascendance of the ninth Inca, or leader, Tupac Inca in 1438. Assuming power after conquering the Chancha

people, he changed his name to Pachacuti.

His name means “earth-shaker,” in the Quechua language he imposed, and

that’s just what he did.

Compared by historians

to Alexander the Great, Pachacuti organized the society and the landscape. He tore down the old city of Cusco, redesigned

it in the shape of the sacred puma, and had it built over decades. The zigzag walls of the fortress or temple

above the city, Sacsayhuaman (meaning “satisfied falcon,”) may represent the

puma’s teeth. Locals say it took 20,000

laborers between fifty and seventy years to build it. Religious fervor and devotion to the state

seem to be the foundation of the extraordinary architecture and road system left

by Pachacuti and his thousands of laborers.

4. Pisac and the Sacred Valley

Our stop in Cusco is

just a tease for a longer stay later. We

board a bus and twist and turn our way twenty miles over the mountains

surrounding Cusco to Pisac. Military

fort, religious retreat, and agricultural area, the setting leaves me

speechless—and breathless. This is our

first stop, but I agree with archaeologist John Hemmer who called this “one of

most spectacular views in the Inca empire.”

Looking over the Urubamba River Valley, known as the Sacred Valley, whose

climate allows farming all year, Pisac’s concave agricultural terraces allow

the sun to heat the stones and warm the earth.

The Incas irrigated the entire farming complex. Restoration workers are the only other people

here, and we watch them painstakingly restore terraces and buildings.

After having this picture taken, I was too winded to catch up to the rest of

the group. Slow and steady was the pace

on this first day at 11,000 feet.

In Urubamba Province,

with a population of about 15,000, from Pisac to Yucay through the Urubamba

River Valley, each town has an economic niche.

Corina points out specific towns that serve barbecued guinea pigs, make

adobe bricks, serve Chicha (corn beer), farm, etc. Kids play soccer near Inca farming

terraces. Informal transportation is

evident throughout the area.

Near the Urubamba River,

there are salt flats where the sea floor rose, trapping sea water. These have been used since ancient times for

salt pans. Red cliffs indicate the

presence of iron oxides—good clay for pottery.

Other areas are good for farming barley and one of Peru’s top exports: quinoa.

Cochineal beetles provide the bright red dye so beautiful in Andean weavings (and so prized by North American colonists who used Cochineal to color wall paint and cloth to show their wealth). Stopping by the side of the road, we sacrifice some beetles to science, harvesting them from the cactus plants on which they thrive, and squashing them in my palm for the edification of the group.

Cochineal beetles provide the bright red dye so beautiful in Andean weavings (and so prized by North American colonists who used Cochineal to color wall paint and cloth to show their wealth). Stopping by the side of the road, we sacrifice some beetles to science, harvesting them from the cactus plants on which they thrive, and squashing them in my palm for the edification of the group.

5. Rafting the Urubamba River and Touring Ollantaytambo

More on agriculture

later—it’s time to go rafting on the Urubamba River. Yes, it’s a touristy thing to do, but now I

can say I have paddled on three continents.

This trip does not rival the beauty of the Li River near Guilin, China,

nor does it rival the Nantahala River in North Carolina, U.S.A., for

class-three whitewater thrills, but it’s the only river I’ve paddled from which

I can view Inca archaeological sites, mostly look-out towers along with

agricultural terraces, some still in use today by local farmers.

This trip is one example of how the tourism industry is transforming the Urubamba River Valley. Our hotel is another. One of a number of eco-tourism and hostel sites along the Inca Trail (in this area, a stone path between villages), it was a beautiful lodge with views that could keep visitors happy for a week. However we are soon off to a new adventure: touring the archaeological site at Ollantaytambo.

Architects and archaeologists can give more detailed accounts of the sites we visit than I will do here as a first-time visitor, and I have listed good resources below for further investigation. It is hard to say where the town of Ollantaytambo ends and where the archaeological site begins—until the Ollantaytambo complex comes into full view.

Breathtaking in a different way than Pisac (and we are getting acclimated to altitude by now), the site’s scale and sizes of the stones are overwhelming. Archaeologists are still trying to learn how the Inca quarried granite not found in this valley, moved it to the site, and built on this huge scale.

I wonder if the visiting

groups of local school children can picture the men, women, and children who

built, farmed, officiated, conducted rituals, and lived in this place as I

can. Do they know that captives, many

from the Lake Titicaca region, provided the forced labor to Pachacuti after he

conquered them? During the building

process, the captives—angry at their base treatment—escaped and led an uprising

against Pachacuti. Scientists and archaeologists

have pieced this information together from Spanish interviews with Peruvians in

the 1570s, and due to the fact that stone carving and joining techniques at

Ollantaytambo reflect the same style as buildings at Tiahuanaco, near Lake

Titicaca. Climbing the steep staircase

alongside the seventeen arc terraces, I am reminded of the Great Wall of China,

another feat of forced labor over decades, the vision of a powerful ruler

carried out by the power of thousands of citizens.

Can the visiting school

children imagine the rebel emperor Manco Inca riding his stolen Spanish horse,

leading the final rebellion against the Spanish conquistadors atop the steep

terraces? He and his forces surprised

the Spanish here in 1536, diverting the Urubamba River through the complex

canal system to flood the plain on which the Spanish rode on horseback—the same

plain on which we now stand. Do they

wonder if the empire would have survived had Manco Inca succeeded in routing

the Spanish? Or do they, as I do, stare

at the walls, terraces, carved fountains, and hillside fortresses and wonder,

“How did they do that?”

Can the visiting school

children imagine the rebel emperor Manco Inca riding his stolen Spanish horse,

leading the final rebellion against the Spanish conquistadors atop the steep

terraces? He and his forces surprised

the Spanish here in 1536, diverting the Urubamba River through the complex

canal system to flood the plain on which the Spanish rode on horseback—the same

plain on which we now stand. Do they

wonder if the empire would have survived had Manco Inca succeeded in routing

the Spanish? Or do they, as I do, stare

at the walls, terraces, carved fountains, and hillside fortresses and wonder,

“How did they do that?” Inca homes in the

traditional part of town are still much the same as they were in the 1500s: one-room

adobe shells. They are laid out in a

grid pattern, with irrigation systems that still work. Some of today’s town residents open their

homes to tourists, and here one can imagine life for an Incan family “back in

the day.” Once our eyes adjust to the

dim light, we first notice the guinea pigs, thirty of them, scurrying to nibble

the barley grass Corina drops at her feet.

“This was my job as a kid—to feed the guinea pigs.” Looking up and on a stone altar, we see

offerings of a dried llama, potatoes, grains, and the sacred coca leaf. An open fire is used for cooking. Aside from the few touristic additions, we

could be living in the early 1500s, under the watchful skull of a beloved

ancestor in a niche above the altar.

Likely, due to its careful layout, this town provided residence to select

members of the Incan hierarchy.

Inca homes in the

traditional part of town are still much the same as they were in the 1500s: one-room

adobe shells. They are laid out in a

grid pattern, with irrigation systems that still work. Some of today’s town residents open their

homes to tourists, and here one can imagine life for an Incan family “back in

the day.” Once our eyes adjust to the

dim light, we first notice the guinea pigs, thirty of them, scurrying to nibble

the barley grass Corina drops at her feet.

“This was my job as a kid—to feed the guinea pigs.” Looking up and on a stone altar, we see

offerings of a dried llama, potatoes, grains, and the sacred coca leaf. An open fire is used for cooking. Aside from the few touristic additions, we

could be living in the early 1500s, under the watchful skull of a beloved

ancestor in a niche above the altar.

Likely, due to its careful layout, this town provided residence to select

members of the Incan hierarchy.

Arriving at our local

hosts’ home for lunch, we offer gifts from our homes for their

hospitality: Michigan cherries, a

Liberty Bell, and school supplies for the children. A chicha

(corn-beer) bar when not hosting tourists, the large table seats guests and

family. Dad is a server at a local

restaurant, Mom runs the chicha

business, one daughter is away in Cusco at college, and other children help

with the cooking and chores after school.

We join Corina and two of the daughters in the outdoor clay-fire kitchen to help prepare an appetizer. Knowing many of us are vegetarian, our hosts have graciously prepared lentils as an alternative to the Peruvian specialty cuy (roasted guinea pig). The meat-eaters’ assessment was vague, “Cuy doesn’t taste like chicken, and it doesn’t taste like rabbit. It’s sort of gamey.” We all enjoy avocado, corn, sweet purple corn beer (unfermented chicha), and conversation over our potatoes and Peru tortillas before thanking our hosts and departing.

- Corina’s Peru Tortilla Recipe (for 15 people). Use other ingredients as desired. This is a flexible, home-cooking recipe that yields something more like a fritter than flat tortilla. Yummy!

1 pound corn meal

2 eggs

½ tablespoon baking soda

1 teaspoon salt

Chop/dice green onion and chili pepper.

Mash 3-4 cooked potatoes.

Combine and mix all ingredients.

Deep fry by tablespoonful in oil until golden brown.

A hop-scotch tournament

complete with announcer and area village women cheering for their players is

our after-lunch surprise. The announcer

shouts with triumph as a woman completes the cycle. He wails with dismay as a woman from another

village misses her mark and has to start over.

The crowd roars either way. Who

knew hop-scotch could be so exciting?

Wandering the streets of

Ollantaytambo we see the intermingling of festival and daily-life

atmosphere. Rural visitors are decked

out in regional dress, while local vendors and shops offer everything from

coffins to brooms, barley grass for guinea pigs to packaged pet food, chickens

to school uniforms. Of course touristic

offerings are evident, as is the high-production pottery studio of Paulo

Seminario. The town is friendly, interesting,

and welcoming, but Machu Picchu is calling.

Wandering the streets of

Ollantaytambo we see the intermingling of festival and daily-life

atmosphere. Rural visitors are decked

out in regional dress, while local vendors and shops offer everything from

coffins to brooms, barley grass for guinea pigs to packaged pet food, chickens

to school uniforms. Of course touristic

offerings are evident, as is the high-production pottery studio of Paulo

Seminario. The town is friendly, interesting,

and welcoming, but Machu Picchu is calling.

6. Machu Picchu, Sacred

City in the Clouds

I am among the first to

board the Machu Picchu-bound train June 19, days before the winter

solstice. Just holding the train ticket

is exciting. Named for Hiram Bingham (the

Yale professor turned explorer who rediscovered Machu Picchu with the help of

locals in 1911), the train travels with gracious tea and snack service from

Ollaytantambo’s 11,000 feet to a comfortable 6,000 feet.

We descend from highlands towards the Amazon jungle, and the plants change accordingly. Bromeliads scale the mountains now. An efficient bus system transports the government limit of 2500 visitors per day up a switch-back road from Aquas Calientes to Machu Picchu, and when our bus pops a tire on the rocky road, a relief bus comes in minutes. We pass through the gates as 3:00 P.M., just as the crowds are leaving. Soon, we will have the place to ourselves.

We descend from highlands towards the Amazon jungle, and the plants change accordingly. Bromeliads scale the mountains now. An efficient bus system transports the government limit of 2500 visitors per day up a switch-back road from Aquas Calientes to Machu Picchu, and when our bus pops a tire on the rocky road, a relief bus comes in minutes. We pass through the gates as 3:00 P.M., just as the crowds are leaving. Soon, we will have the place to ourselves.

“What was man? Where in

his simple talk

amid shops and whistles, in which of his metallic motions

lived the indestructible, the imperishable—life?”

amid shops and whistles, in which of his metallic motions

lived the indestructible, the imperishable—life?”

In The Heights of Macchu Picchu, Nobel Prize-winning poet Pablo Neruda

wrote these words as he pondered his visit to Machu Picchu. Is that what we are looking for—the

imperishable? We seem to be finding it

here. The light. The ring of

mountains. The blue sky. The green grass. The stone work. The sheer slopes. The Urubamba River roaring below. The massive scale. Machu Picchu is stunning. We don’t know where to begin.

As much as one prepares

to visit Machu Picchu, the effect of being here is wondrous. Yes, we’ve read conflicting accounts of its

purpose: administrative center, Pachacuti’s imperial retreat, agricultural

center, sacred city. Among the possible

uses, with its complete integration into its natural surroundings, the place

seems perfect for a religious retreat and sacred worship of the sun, stars,

mountains, and rivers.

Corina affirms this

observation with her introduction. It

was a sacred place for the Incas, close to the Apus (sacred mountains), near the Sun, with the Urubamba River

curving in a horseshoe at the base of the mountain. “It’s a sacred place. Like Mecca or Jerusalem,” she says. She shares speculation about why it was

abandoned before the Spanish could get wind of it and sack it. Built on two fault lines, was it

earthquake? Flood? Disease?

She describes the

massive earthmoving project to build foundations for buildings and to enrich

soil for agriculture. Incan laborers and

llamas brought thousands of pounds of guano (bird droppings) from massive

deposits on the coast near today’s Lima hundreds of miles away. The resulting terraces (forty on one hillside

alone) were farmed to grow tons of maize, chili peppers, peanuts, potatoes, and

other crops for the estimated 800 people living here. Including the surrounding mountains, the

complex covers 64,000 acres. And that is

an important point: Machu Picchu is not a site in isolation. Archaeologists continue to discover other

sites nearby, with direct connection to Machu Picchu.

Sacred mountains are

clearly visible in each of the cardinal directions: Pumasillo is to the west,

Veronica (Wkay Willka) is to the east, Salcantay is to the south, and Huayna Picchu

is to the north—close enough to touch.

Temples, windows, and the famed Intihuatana, (Hitching Post of the Sun), are oriented to catch rays of the sun at solstices, to orient at night to the Southern Cross and to the sacred Pleiades. These would have helped the Inca in worship and in planning the agricultural year. Precise orientation to light, mountains, and water is everywhere.

Temples, windows, and the famed Intihuatana, (Hitching Post of the Sun), are oriented to catch rays of the sun at solstices, to orient at night to the Southern Cross and to the sacred Pleiades. These would have helped the Inca in worship and in planning the agricultural year. Precise orientation to light, mountains, and water is everywhere.

Stonework is the lasting

legacy of Incan artifact. Incas kept

records orally and with quipus,

intricately knotted ropes in a series that archaeologists do not yet know how

to decode. Without a written language,

the buildings at sites like Machu Picchu tell us what we know about the Incas

more than almost any other source.

Spanish chroniclers are not always dependable, although their interviews

with Incan and other tribal elders during the conquest provide much

information. Therefore, we study rocks that

are formed in tight rows or courses, shaped into joints and cornices, carved in

impossible angles. In some places, like

the so-called “mausoleum” beneath the curved Torreón tower outcrop, the granite boulder has been carved into

steps on one side. Stone walls seem to

spring seamlessly from it on another.

Bingham gave sections of

the city names: agricultural group, temple complex, and manufacturing

complex. We make our way among them,

Corina pointing out angles in the way the light comes through a typical trapezoidal

window, two reflecting pools ready to catch the first sunlight on the solstice,

and the one temple building whose foundation has shifted after all the centuries

since it was constructed.

Llamas,

remaining from a movie shoot, Corina says, meander over to see if we have food

in our backpacks. Workers weed-whack

terraces and flatten the paths. A UNESCO

World Heritage Site, soft-spoken guards are ready to restore order if visitors

act in a way “disrespectful to the national identity.” There is no need in our case. Corina worked on site at Machu Picchu for

years and greets fellow guides and guards alike. The fourteen of us are reverent visitors. Pretty soon, except for the llamas and

employees, we are the only ones here.

Along with the light, the silence is magical.

We stay overnight in

noisy Aguas Calientes, across from a soccer stadium whose competitors and

crowds want soccer live rather than to glue themselves to TV screens to watch

the ever-present World Cup matches. We

realize that the numbers of South American tourists are down at Machu Picchu,

because so many have gone to Brazil. We

have the best of both worlds: silence at Machu Picchu, and great fútbol

matches on TV everywhere we look. We retire

early to sleep—those of us lucky enough to have rooms away from the street’s

endless bar noise. We are returning to

Machu Picchu before dawn to watch the sunrise at the winter solstice.

“Then on the ladder of

the earth I climbed

through the lost jungle’s tortured thicket

up to you, Macchu Picchu.

High city of laddered stones,

at last the dwelling of what earth

never covered in vestments of sleep….”

through the lost jungle’s tortured thicket

up to you, Macchu Picchu.

High city of laddered stones,

at last the dwelling of what earth

never covered in vestments of sleep….”

The magic of the sun’s

rays breaking atop Mt. San Gabriel soon yields to the reality of daylight at

Machu Picchu. World Cup or no, tourists

stream into the site with the force of Disneyland visitors. German, Japanese, Chinese, Australian,

Brazilian, Argentinian, Peruvian, U.S.—the world’s travelers are well represented

here.

Returning to the main site, I find the buildings, shrines, and terraces I was beginning to recognize yesterday are unrecognizable in this brilliant morning light. I wander aimlessly, merging with multicultural streams of tourists. I find the so-called Funerary Rock shrine, solitary in the sun atop a peaceful plateau. We rediscover the Intihuatana, Hitching Post of the Sun, looking so different when oppositely lit and shadowed. We watch workers catch a pregnant llama, getting her medical assistance for a difficult delivery. Guards resume their vigils, this time with real numbers to manage. We reunite with our small group, and I take one last jump for joy after touring this remarkable city in the clouds. But, like Neruda in his poem, I am pondering the hands that built this place.

“You’re no more now,

spidery hands, frail

fibers, entangled web—

whatever you were fell away: customs, frayed syllables, masks of dazzling light.

Yet a permanence of stone and word,

the city like a bowl, rose up in the hands

of all, living, dead, silenced, sustained,

a wall out of so much death, out of so much life a shock

of stone petals: the permanent rose, the dwelling place:

the glacial outpost on this Andean reef….”

fibers, entangled web—

whatever you were fell away: customs, frayed syllables, masks of dazzling light.

Yet a permanence of stone and word,

the city like a bowl, rose up in the hands

of all, living, dead, silenced, sustained,

a wall out of so much death, out of so much life a shock

of stone petals: the permanent rose, the dwelling place:

the glacial outpost on this Andean reef….”

7. Worshipping with Incans and Dominicans: The Qoricancha

Returning to Cusco at

night, we ride into town on the smugglers’ street, where truckloads of

contraband goods from Bolivia are unloaded into stores of all sorts, from

electrical to grocery. Government

subsidized Bolivian items are cheap, and they are in great demand in Peru. “Everyone knows, and no one says anything,”

says Corina.

In the morning, we pass

community groups assembling papier-mâché floats: the New Year’s party has

continued while we were in Machu Picchu, and today it will be in full

swing. Having acclimated to the

altitude, we can breathe easily now, even though we’re back at 11,000

feet.

First, we have some archaeological

detective work to do, in Cusco’s holiest site: the Qoricancha (Coricancha) Sun

Temple. We encounter the rare curved

Inca wall, indicating utmost holiness. Pachacuti,

the earth-shaker Inca, had ordered this temple built upon an earlier temple, basalt

stone was quarried from twenty to forty miles away, according to different

sources. Center of all Inca worship, and

center-most in the empire of all connected Inca shrines, the Qoricancha was

covered in gold. Different rooms honored

various gods, from Sun, to Moon, to Lightning and Thunder, to Rainbow.

The finest stonework in the empire is evident—and possibly—finest in the world at the time. These are among the stone walls joined without mortar, the joints of which “not even a razor blade or paper can pass,” as the tour books say. There are grooves, peg holes, indentations and angles carved into the stone joints. These would be invisible but for the fact that the Spanish conquistadors dismantled the temple and quarried the stones to build a Dominican church atop the Incan foundation walls.

The finest stonework in the empire is evident—and possibly—finest in the world at the time. These are among the stone walls joined without mortar, the joints of which “not even a razor blade or paper can pass,” as the tour books say. There are grooves, peg holes, indentations and angles carved into the stone joints. These would be invisible but for the fact that the Spanish conquistadors dismantled the temple and quarried the stones to build a Dominican church atop the Incan foundation walls.

In 1532, when Francisco

Pizzaro and 168 Spanish adventurers intruded on the Incan imperialist state

with their own imperialist adventure, the Incan empire was emerging from civil

war. As Jared Diamond explains in Guns, Germs, and Steel, the outnumbered Spanish

had several advantages over the numerous and highly organized Incas. First, European-born diseases like smallpox

and measles came with them. Indigenous

people had no immunity to these new diseases and died by the thousands. Second, the Spanish came with steel swords,

had simple guns, and rode horses, weapons and animals the Incas had never seen. Finally, the Incan empire was in

disarray. European disease had claimed

the life of the supreme Inca and his intended heir. Two brothers fought for the throne, and

Atahualpa won.

Soon thereafter, Atahualpa,

the twelfth Inca, lost the empire. Feeling

invulnerable perhaps against a small force of bearded strangers and their

enslaved African and Indian companions, Atahualpa agreed to meet Pizzaro, who

promptly kidnapped him. Atahualpa

offered a huge ransom of silver and gold, which the Spanish soon stripped from

such places as Qoricancha. Spanish

sources described 700 sheets of gold, adorned with precious stones. Life-size gold and silver statues of llamas,

sheet, humans, and plants were removed.

The treasures of the

kingdom were melted down and shipped to Spain, Atahualpa was executed anyway,

and the warring tribes grudgingly under Inca dominance were all too happy to

help the Spanish exterminate their now-weakened foes. It is estimated that the indigenous

population may have been twelve million before 1532. After the ensuing wars, forced mining, and

epidemics, one hundred years later a census estimated 600 thousand.

Dominicans built their

church atop the Sun Temple, but it is the Incan structure that has survived two

earthquakes. The Iglesia Santo Domingo has had to be rebuilt. Neither could the Catholic Spaniards entirely

shake the religious foundation of the Incan people. Yes, many Incans became Catholic, but Andean

Catholicism today is still inclusive of reverence for the Apus, Pachamama, and Inti. We see evidence in the work of the

Cusco School of Painters, with another 1600s version of the Last Supper, by Marcos Zapata, in which

Jesus and his disciples again dine on cuy

along with Andean vegetables. The

Catholics tried to turn veneration of the sun, Inti Raymi (celebrated at the winter solstice on June 21) into a

feast for John the Baptist by moving the feast to June 24. This

change did not diminish the Andean spirit at all. The more to venerate, seemingly, the merrier!

We hike uphill through

Cusco’s famous stone streets, to the San Blas neighborhood for a snack at Pachapapa’s and some browsing at the

local craft fair. Shopping is

overwhelming, as everything is beautiful, from the painted pottery plates, to

the carved gourds, to the omnipresent weaving.

We buy a few gifts, exchange some sign language with vendors about our

respective children, and head back downhill.

We hike uphill through

Cusco’s famous stone streets, to the San Blas neighborhood for a snack at Pachapapa’s and some browsing at the

local craft fair. Shopping is

overwhelming, as everything is beautiful, from the painted pottery plates, to

the carved gourds, to the omnipresent weaving.

We buy a few gifts, exchange some sign language with vendors about our

respective children, and head back downhill.

In Plaza de Armas the party continues.

It’s been days now! Floats are

fully assembled and community groups parade them past the judging stand, some

accompanied by small bands. As a Philly

girl, I am reminded of my home-town Mummers’ Parade. There, too, neighborhood groups create

costumes, floats, and music and compete for the judges’ (and crowd’s)

affections. We climb onto the balcony of

an English-style pub, glancing at the ceiling of world flags. The patrons are oblivious to the party on the

street; most are screaming for Argentina in the World Cup game. Looking onto the joyous scene below,

listening to energetic flutes and drums—punctuated with shrieks from the pub

crowd as the goalie saves the day: again we enjoy the best of both worlds.

Food. We’ve been eating tasty restaurant food with

beautiful presentation. Ceviche, almost a Peruvian national

dish, is one new discovery: raw fish marinated in a mixture of lemon juice,

onion, peppers, and salt. Often our

hosts are at a loss to serve vegetarians.

A common solution is vegetable kabobs.

Delicious quinoa soup with a matzo-ball-like

potato is hearty meal. Avocado—in

salad—or alone is a delight. Always there is corn, or several varieties of potatoes, or both. Aji, flavorful peppery hot sauce, is to die for. Sometimes there is a delicious snack of cancha, fried corn kernels, or choclo, boiled chunks of large-kernel corn.

Many of us don’t drink alcohol, so the ubiquitous pisco sour offerings are lost on us. The unfermented corn beer, chicha morada, is very sweet and very purple. Another sweet offering is Inca Kola, in vending machines and street corners everywhere. The coffee is strong and delicious, and Corina was right: mate de coca, coca tea, is everywhere. I’ve been drinking it everyday, and it tastes like the herbal remedy it is. Always we drink agua, water, either con gas, carbonated, or sin gas, uncarbonated.

Many of us don’t drink alcohol, so the ubiquitous pisco sour offerings are lost on us. The unfermented corn beer, chicha morada, is very sweet and very purple. Another sweet offering is Inca Kola, in vending machines and street corners everywhere. The coffee is strong and delicious, and Corina was right: mate de coca, coca tea, is everywhere. I’ve been drinking it everyday, and it tastes like the herbal remedy it is. Always we drink agua, water, either con gas, carbonated, or sin gas, uncarbonated.

It’s when we visit San

Pedro Market, humming on a Sunday morning at the holidays, that we see what

daily food looks like. Corn—popped,

dried, in all permutations is evident. Vendors

cut sugar cane, with cane presses ready to squeeze a refreshing drink. Interspersed with flowers, fruits, and

vegetables are common everyday footwear in the mountains: “forever sandals,”

so-called because they’re made from old tires and last forever. Avocadoes, limes, pomegranates, tangerines, and

plums are piled high.

It’s the meat aisle that

gives me pause. Hooves, hearts, and

intestines are on display, and the typical sheep’s head soup is for sale in

booths with benches for diners. I turn

into another aisle and find flour, beans, vegetables, chocolate, and coca

leaves, chewed by Andean locals and used as offerings in ceremonies. Breads in huge round loaves mingle with

smaller flat breads. We buy a loaf to

eat on the bus and exit to see a festival set up for the kids. And guess what—there’s a parade going on in

the street. One costumed community group

marches by with a band. Another practices

the dances it will perform later in the day.

9. Rehearsing in Sacsayhuaman

How would you go about moving a boulder twelve miles uphill? Would its size of sixteen-by-fifteen-by-eight feet, and its weight of ninety metric tons intimidate you? From Hemming and Ranney’s Monuments of the Incas, here’s how the Incas moved mountains on the hill above Cusco at Sacsayhuaman, according to chronicler (and grandson of Incas) Garcilaso de la Vega, writing in 1609:

How would you go about moving a boulder twelve miles uphill? Would its size of sixteen-by-fifteen-by-eight feet, and its weight of ninety metric tons intimidate you? From Hemming and Ranney’s Monuments of the Incas, here’s how the Incas moved mountains on the hill above Cusco at Sacsayhuaman, according to chronicler (and grandson of Incas) Garcilaso de la Vega, writing in 1609:

“Learned Indians…affirm

that over twenty thousand Indians brought up [the largest] stone, dragging it

with great cables. Their progress was

very slow, for the road up which they came is rough and has many steep slopes

to climb and descend. Half the laborers

pulled at the ropes from in front, while the rest kept the rock steady with

other cables attached behind lest it should roll downhill.”

The 415-yard-long rows

of zigzag walls at Sacsayhuaman formed the teeth of the puma shape in which

Pachacuti constructed Cusco. They were

assembled in typical tight-fit manner, consisting of hundreds of such boulders,

or “lumps of mountains,” as Garcilaso called them. Sixty-five million years ago, they were at

the bottom of the sea.

Fortress, storage

center, holy site, Sun temple, Sacsayhuaman was so impressive that Cieza de

Leon wrote in 1550, “[It] was so strong that it will last for as long as the

world exists.” Or, as long as it took

the Spanish conquistadors to dismantle it so they could use the stones to build

their houses. About fifty percent of the

original construction remains: the walls, foundations of the towers and water

supply canals, and the underground tunnels reportedly leading to a maze of

rooms.

The Peruvian army is

here today. In the brilliant sun, just

after the winter solstice, they are singing, dancing, chanting, bowing, and

praying as they rehearse their parts for the intricate re-enactment of Inti Raymi (Sun Festival). Based on Spanish accounts of the festival as

they observed it in the 1500s, the revived festival is a procession of the

great Inca, his court, guards, and other public officials.

Women and men chant ceremonial songs, their

mournful voices pleading with the sun to return after its shortest day of the

year. During the ceremony, fires will be

lit, intricate costumes will be worn, and the music and dancing that has filled

Cusco for days will yet again be on display.

We are backstage in a great out-door opera, one with spiritual meaning

for an empire.

Taking our obligatory

photos with the extraordinary boulders, we move into another spiritual realm

nearby, a visit with a traditional healer or curandero. Our new spiritual

brother assembles various offerings of such items as sweets, grains, corn beer,

and coca leaves to Pachamama. He invites us to make intentions and prayers

with the offerings of three coca leaves each, blesses us with them, and burns

the package of offerings in solemnity.

Meanwhile, families set

up tents and what Corina affectionately calls “Peruvian microwaves” on the

hillside park above Cusco. They dig a

hole, build a fire, put in potatoes to roast, and cover with dirt. While they wait for their potatoes to roast,

they play volleyball, chase dogs, buy snacks, and relax as they await Inti Raymi and the new year. The white statue of Jesus on the hillside

presiding over the scene? It was a gift

from Palestinian Christians, who were granted refuge in Peru in 1945.

10. Controversies in Chinchero and Going to School

On our way to visit a

weaving cooperative and a rural school, Corina’s open personality and Peru’s

relative stability allow her to share numerous details and controversies of

recent Peruvian economic and social development. Take the controversy over cocaine. Cocaine is a North American problem, she

argues. The coca plant is like the grape

plant. Wine is a processed product of

grapes, and cocaine is a processed product of coca plant. Numerous legal uses abound, including

Andeans’ daily use to combat the effects of altitude as well as other medicinal

uses for which Peru exports coca leaf to the U.S. Illegal uses of the drug are completely

separate from traditional uses, she says.

Peruvian foods—mainly some of the 4000 varieties of potatoes developed by Andean peoples—changed the world during the Columbian exchange. Read Charles Mann’s 1493 to see how potatoes stopped starvation in Europe and led to European population booms and global ascendance from the 1600s to 1800s. In 1493, you can also read about the effect of Peruvian silver and guano (nitrate-filled bird droppings used as fertilizer) on the Columbian-exchange world as well.

Now, in today’s

globalized food supply, think about quinoa.

Along with Bolivia, Peru is the number one exporter of quinoa, the new

super-food, with twice the protein of rice.

Of course, it’s not new to the Andean people, who are working to protect

their ownership of the hereditary seeds, keeping multinational agro-corporations

from stealing their ancient birthright. Listen

to the National Public Radio news stories on the complexity of the global quinoa

boom for Andean farmers and consumers.

Peru imports rice from

China, sugar from Bolivia, oil from Ecuador and Venezuela, cars from Japan and

Korea. Exports—especially to Europe and

the U.S., are headed by Peru’s organic agriculture products, mainly tomatoes,

potatoes, artichokes, asparagus, and recently, blueberries. Despite numerous mineral resources, Peru is still

developing economically, and great class disparities exist. They are evident as we contrast suburban

Miraflores with “suburban” Chinchero.

The air is clear and the high lake, surrounded by mountains, blue sky,

and brown, tan, and green fields is an inviting place to stretch our legs. I imagine life here as I look longingly at

the three canoes tied near shore.

We approach Chinchero,

where high farmland farmers are burning fields.

There are few cars, hundreds of varieties of potatoes, and lots of fava

beans. Amidst the quilt work of fields,

the government is building a new international airport. There is much corruption as the government

pays farmers far less for land than is recorded. I wonder how families accustomed to open

spaces and proximity to Pachamama

will fare in the new concrete apartments under construction.

Those of us old enough

to remember have heard of the neo-Maoist Shining Path, or Sendero Luminoso. Amidst the

discontent during the economic and agrarian crises of the 1980s, college

professor Abimael Guzmán tried to revolutionize Peruvian society, aiming to

abolish the divisions of rich and poor. He

formed Shining Path, but the group’s violent techniques terrorized rich city-dwellers

and poor village people alike. Corina

remembers from her village days the fear that Senderistas would kidnap young boys, steal sheep, and use other

violent means to coerce cooperation from villagers. Car bombs and attacks on bridges,

hydro-electric plants, and international investment projects followed. The ensuing years saw thousands of Andean

villagers die as they were caught between the violence perpetrated by the Peruvian

military and Sendero Luminoso

guerillas. The crisis was compounded when

another revolutionary group, Tupac Amaru,

came on the scene.

Those of us who followed

these developments from afar remember when Alberto Fujimori came into power in

1990. During his first term he captured Guzmán,

breaking the back of Shining Path. In

his second term he undermined Tupac Amaru, ending their 126-day hostage-taking

occupation of the Japanese ambassador’s home in Lima. Fujimori promoted education and cut

illiteracy. He built healthcare and road

infrastructures. Everyone loved

him. Until they discovered the

dictatorial policies he was also undertaking.

Locals among the farming

communities through which we are driving long remember. During a 1997 “family planning” drive, for

example, women had their fallopian tubes tied against their wills. They are known as the Women of Anta. Fujimori forces killed one of Corina’s

college professors in front of her class.

She left the country shortly thereafter.

Fujimori fled the country too, although he has since been returned and

is serving a forty-year term for human rights abuses.

Locals among the farming

communities through which we are driving long remember. During a 1997 “family planning” drive, for

example, women had their fallopian tubes tied against their wills. They are known as the Women of Anta. Fujimori forces killed one of Corina’s

college professors in front of her class.

She left the country shortly thereafter.

Fujimori fled the country too, although he has since been returned and

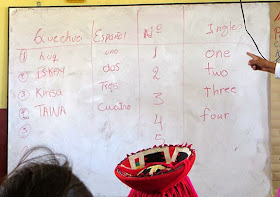

is serving a forty-year term for human rights abuses.Our fifth grade hosts stand out from the children in grades one to six. In our honor, instead of the mandatory school uniform, our hosts wear bright red ponchos and vests, their traditional festival costumes. Ten-year-old Jefferson is my guide. After our introductory lesson in Quechua, we look around the room to appreciate their math problems and geography studies. The children take turns introducing themselves to the group in Spanish, telling us their desires to be doctors, lawyers, teachers, soldiers, and police. No child mentions farming as an aspiration.

We have a short

question-and-answer session. We ask

their daily schedule. “Get up, wash,

brush teeth, go to school, and then help our parents in the store or farm.” They ask, “Who is taking care of your animals

while you’re traveling?” We have to

explain that we have no sheep or llamas at home, only cats and dogs the

neighbors care for.

Education is mandatory

in Peru, from ages six to eleven. In the

highlands, students start learning in Quechua, continuing in Spanish. Primary school, for ages six to eleven, is followed

by five years of secondary, and at ages fourteen to sixteen, an exam to gain

entrance to college or technical track. UNESCO

2007 statistics indicate adult literacy in Peru is 89.6%, while youth literacy

(ages 15-24) is 97.4%. In rural areas, thirty

percent of students might go to technical school, ten percent to college. Like Canadians, Peru’s students attend

college for five years. After college,

will they return to the highlands as adults as these teachers and principal and

our tour guide have?

Every student in school

lines up to receive gifts of oranges and bananas, a treat to a highland child,

Corina tells us. The principal is beaming. The children perform

for us, their honored guests. One girl,

a future valedictorian, declaims dramatically in Spanish her love for education. Two boys sing a song. The group dances a traditional dance, with

their teachers playing spiritedly on traditional drums and flutes. Their education, in Spanish and Quechua,

clearly encompasses both histories.

Every student in school

lines up to receive gifts of oranges and bananas, a treat to a highland child,

Corina tells us. The principal is beaming. The children perform

for us, their honored guests. One girl,

a future valedictorian, declaims dramatically in Spanish her love for education. Two boys sing a song. The group dances a traditional dance, with

their teachers playing spiritedly on traditional drums and flutes. Their education, in Spanish and Quechua,

clearly encompasses both histories.

I have brought a gift

from my students who wrote poems of peace for their unseen friends in

Peru. We have created them on cloth, similar

to the prayer flags of Nepal, and inspired by Jeff Harlan and Sandy Crowe’s

Dream Flag Project, connecting the hopes and dreams of children all over the

world. The children will create their

own poems to send back to my students, and Corina will pick these up on her

next visit. We take one last photo with

flags of peace unfurled, the snow-capped Andes Mountains behind us. We hug the energetic principal and our small

hosts and depart, leaving this 12,500-foot literal and figurative highpoint of

our trip.

11. Weaving: Better than Gold

Readers may be

wondering, “How can she write about the Incas and their descendants without

writing about weaving?” I have saved the

best for last. Stonework, temples,

forts, cities, roads may be the lasting creation of Incan men, but weaving

remains the lasting legacy of Incan women.

Readers may be

wondering, “How can she write about the Incas and their descendants without

writing about weaving?” I have saved the

best for last. Stonework, temples,

forts, cities, roads may be the lasting creation of Incan men, but weaving

remains the lasting legacy of Incan women.

Two stops at weavers’

cooperatives show us the mastery of Andean weavers: one at the Centro de Textiles Tradicionales de Cusco,

and the other in Chinchero. In Cusco,

male and female master weavers from surrounding rural areas spend a week living

in the museum, demonstrating their techniques to visitors, sharing their

designs with each other, and honoring the weaving tradition. Next to the showroom an informative museum displays

the woven clothes that accompany each milestone in a highlander’s

lifespan.

Two stops at weavers’

cooperatives show us the mastery of Andean weavers: one at the Centro de Textiles Tradicionales de Cusco,

and the other in Chinchero. In Cusco,

male and female master weavers from surrounding rural areas spend a week living

in the museum, demonstrating their techniques to visitors, sharing their

designs with each other, and honoring the weaving tradition. Next to the showroom an informative museum displays

the woven clothes that accompany each milestone in a highlander’s

lifespan. In Chinchero, our weaving cooperative has also been formed to keep the rich tradition alive. Our hosts try to teach us each intricate step. Videos linked below will help readers understand the lengthy process of collecting flowers, cleaning wool, spinning yarn, and dying it, before the weaving process—conducted in any number of ways—even begins. The geometric designs have significance: an-S-curve may indicate a river, a circle—a lake; the traditional pattern indicates the village in which the weaver lives (as it did long ago). A rectangular cloth might take a month or more to weave, depending on the patterns’ detail.

In the Inca time, in addition

to running the household and weaving clothes for her family and herself, every

woman’s mit-a (required work), was to

produce one piece of woven clothing for the state’s storage. The Spaniards valued gold, but the Incas

valued fine weaving above gold, according to such chroniclers as the part-Incan

Garcilaso de la Vega. Cloth-production

was second only to agriculture as an industry.

Textiles were used as offerings to the gods, as payment to soldiers, as

gifts to nobles, and as indication of rank.

In the Inca time, in addition

to running the household and weaving clothes for her family and herself, every

woman’s mit-a (required work), was to

produce one piece of woven clothing for the state’s storage. The Spaniards valued gold, but the Incas

valued fine weaving above gold, according to such chroniclers as the part-Incan

Garcilaso de la Vega. Cloth-production

was second only to agriculture as an industry.

Textiles were used as offerings to the gods, as payment to soldiers, as

gifts to nobles, and as indication of rank.

Peru was a cotton

culture for thousands of years prior to Incan ascendancy, and Garcilaso reminds

us that women were weaving both cotton and wool in Inca times, depending on

their climate. He also describes

fifteenth century multi-tasking among women, as they were “so reluctant to

waste even a short time that as they came or went from the village to the

city…, they carried equipment for the two operations of spinning and

twisting….” On the streets of Chinchero, we saw women doing the same thing in

2014.

12. Reflections

“The dead realm lives on

still.

And across the Sundial like a black ship

the ravening shadow of the condor cruises….”

And across the Sundial like a black ship

the ravening shadow of the condor cruises….”

We walk past the potatoes drying in the sun to the Chinchero

retreat Inca Topa Yupanqui built for himself around the year 1500. At first we just see the courtyard of a

church, but upon closer inspection we appreciate the wall of twelve niches, the

terracing down the hillside, the stone shrines, and the atmosphere of peace

still present today.

We are about to board our bus back to Cusco, to fly to Lima and modernity, so we take one last look at the beauty of Chinchero. How will it fare when the international airport opens? How will traditional values that have lasted hundreds of years continue in competition with encroachments of tourists, and television, and technology? “The old must make way for the new,” a Chinese proverb proclaims. Will this hold true in twenty-first century Peru as it did when the Spanish arrived?

We are about to board our bus back to Cusco, to fly to Lima and modernity, so we take one last look at the beauty of Chinchero. How will it fare when the international airport opens? How will traditional values that have lasted hundreds of years continue in competition with encroachments of tourists, and television, and technology? “The old must make way for the new,” a Chinese proverb proclaims. Will this hold true in twenty-first century Peru as it did when the Spanish arrived?

Or did it? Does the survival of Andean arts, beliefs,

farming techniques, family warmth, sharing and bartering, and strong community

values bring the old ways along with the new?

Other lingering questions

involve my quandary in admiring great work produced by forced labor. Like the Great Wall of China, or the U.S.

White House, for that matter, most of the archaeological wonders I admire in

Peru were envisioned by powerful leaders and brought to life by captive, enslaved,

or mandatory labor.

My visit to Machu Picchu

and my trip to Peru’s highlands make me question my assumptions—and my

teaching—about those who lived and worked long ago: emperor, noble, commoner,

and slave. Neruda’s words echo my mental

pictures and wordless queries:

Macchu Picchu, did you

set

stone upon stone on a base of rags?

Coal over coal and at bottom, tears?

Fire on the gold and within it, trembling, the red

splash of blood?

Give me back the slave you buried!

Shake from the earth the hard bread

of the poor, show me the servant’s

clothes and his window.

Tell me how he slept when he lived….”

stone upon stone on a base of rags?

Coal over coal and at bottom, tears?

Fire on the gold and within it, trembling, the red

splash of blood?

Give me back the slave you buried!

Shake from the earth the hard bread

of the poor, show me the servant’s

clothes and his window.

Tell me how he slept when he lived….”

My unease leads me to

ask, “What is a great civilization? Is

it its rulers? Or is it its people?” Recognizing the sacrifices of the past “unknowns,”

can we bring them to life by remembering them?

Can we recover the best of the past to shape the best of the future? In admiring Machu Picchu and the stone

constructions of the Incas, can I remember and nurture the resilience of the

human spirit? Can I accept the fact that

the Incan empire was mercilessly imperialist and also appreciate and rekindle

the spirit of sharing, cooperation, and concern for each member of society its

people engendered?

Neruda remembers the

unknown, unnamed, shadow builders of history and offers to speak for them:

“Jack Stonebreaker, son

of Wiracocha,

Jack Coldbiter, son of the green star,

Jack Barefoot, grandson of the turquoise,

Rise to be born with me, brother….

Jack Coldbiter, son of the green star,

Jack Barefoot, grandson of the turquoise,

Rise to be born with me, brother….

Look at me from the

bottom of earth,

plowman, weaver, voiceless shepherd….

I come to speak through your dead mouth….”

plowman, weaver, voiceless shepherd….

I come to speak through your dead mouth….”

Long after the Incan

empire fell, historians recognize the enduring reminders of Incan society. Archaeologist Michael Malpass observes, “The

sense of common culture that millions of Andean people share today is more the

result of the Incas’ policies than those of the Spaniards…. Thus it is difficult

to say that the Incas no longer exist….” When I ask my new friend Corina Duran

what she most wants my students to know about her people she immediately

replies, “We are not dead. We are very

much alive.” And that, along with a continuing

series of questions, a sense of wonder at the accomplishments of human beings,

and appreciation for the resilience of the Andean people is the resounding

message from my trip to Peru.

—Susan Gelber Cannon, August 2014

—Susan Gelber Cannon, August 2014

LINKS & RESOURCES:

I. General

Introduction to New World/Old World Contact and Introduction to Peru

Websites and Books:

Websites and Books:

1. WEBSITE: LIMA EASY Travel info and tourist/cultural site info, deeply-linked site. http://www.limaeasy.com

2. WEBSITE:

BBC News Country Profiles: Peru http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/americas/country_profiles/1224656.stm

3. BOOK: Insight Guide Peru: http://www.insightguides.com/product/insight-guides-peru/9781780050973

4.

BOOK: DK Eyewitness Travel Peru: http://www.dk.co.uk/nf/Book/BookDisplay/0,,9781409385790,00.html?strSrchSql=travel/DK_Eyewitness_Travel_Guide:_Peru

5. BOOK/PDF: 1491: New Revelations of the Americas

Before Columbus, (Charles C. Mann, 2006) http://www.charlesmann.org/articles/1491-Atlantic.pdf

6. BOOK: 1493:

Uncovering the New World Columbus Created (Charles C. Mann, 2011)

7. BOOK/WEBSITE: Guns, Germs, and Steel (Jared Diamond, 1997) Website of documentary: http://www.pbs.org/gunsgermssteel/

8.

WEBSITE:

ZinnEd Project: Countless resources for

teaching U.S. history emphasizing the participation of those usually left out

of textbooks: http://zinnedproject.org

9.

WEBSITE:

Rethinking Columbus: Classroom

readings and resources for teaching about the Columbian Exchange: http://zinnedproject.org/2011/10/rethinking-columbus-day/

II. Lima

1.WEBSITE:

Villa El Salvador: City Traveler article on Villa El Salvador, Lima, Peru:http://www.thecitytraveler.com/2009/11/lima/

2. VIDEO:

Huaca Pucllana three minute video tour in English and Spanish with subtitles: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ToqaSz8GSZ8

3.

WEBSITE:

Lorca Museum AWESOME online catalogue and exhibit of pre-Inca: http://www.museolarco.org/en/ AND via Google Plus: http://www.google.com/culturalinstitute/collection/museo-larco?projectId=art-project

4.WEBSITE:

Monasterio de San Francisco: http://www.museocatacumbas.com/english/index_en.html

III.

Who Were the Inca? Pachacuti’s Projects

1. BOOK:

Monuments of the Incas (John Hemming

& Edward Ranney, 2010) Beautifully photographed, numerous Incan

architectural/archaeological sites are described and explained. You will understand more about Incan design,

construction, and belief than you thought possible after reading this book and

studying the photos and site plans.http://www.photoeye.com/bookstore/citation.cfm?catalog=NT279

2. BOOK:

The Way People Live: Life Among the Inca (James

A. Corrick, 2004) Basic explanations of daily life.

3. BOOK:

Daily Life in the Inca Empire

(Michael A. Malpass, 2009) Detailed explanations of daily life and ancient and

modern impact of the Incas.

4. WEBSITE:

National Geographic Article on Incas (with links to a photo gallery, simulated

flyover, 1913 Hiram Bingham article and photos, etc.) http://ngm.nationalgeographic.com/2011/04/inca-empire/pringle-text

5. WEBSITE:

National Geographic Interactive Map of Inca Empire 1500s: http://ngm.nationalgeographic.com/2011/04/inca-empire/interactive-map

6.

WEBSITE:

Interactive information game about the Incas: www.nationalgeographic.com/ngkids/games/brainteaser/inca/inca.html

7. PDF:

Quipus Cracking the Khipu Code—Charles

Mann article from Science Magazine: http://www.charlesmann.org/articles/Khipu-Science.pdf

IV. Cusco, Pisac, Urubamba

River, Sacred Valley, Ollantaytambo

1.

VIDEO:

Young dancers in Cusco as part of New Years festivities 2012: (3:30 minutes) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VjGSeM4Nhf0

2. VIDEO: Knowledge, skills and

rituals related to the annual renewal of the Q'eswachaka bridge

The Q'eswachaka rope suspension bridge crosses a gorge of the

Apurimac River in the southern Andes. Four Quechua-speaking peasant communities

assemble annually to renew it, using traditional Inca techniques and materials.

(Ten-minute video) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9xCpAy_8p3U

3. VIDEO: (Five-minute

video) NOVA: GRASS BRIDGE building with background on suspension bridges, questions,

and active teaching activity (excerpt from Nova’s

Secrets of Lost Empires: Inca) http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/nova/education/ancient/grass-bridge.html

4.WEBSITE: Inca stone moving Nova program question and answer: http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/nova/inca1/qanda.html

V. Machu

Picchu

1. WEBSITE: NOVA-Machu

Picchu: A Marvel of Inca Engineering Interview with civil engineer

Ken Wright. Also has informative

interactive links on Inca/Spanish warfare, rise of the Inca, etc. http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/nova/ancient/wright-inca-engineering.html

2. VIDEO:

NOVA-Ghosts

of Machu Picchu: Why did the Incas abandon their city in the clouds?

(One-hour video program with transcript) http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/nova/ancient/ghosts-machu-picchu.html